The Natural City

Follow ArchaNatura On Facebook and Twitter

Today, we have the opportunity to create far happier and healthier human life.

This goal or desire of course is not new. What is new is our growing modern accumulation of health-related science – physiological, psychological, sociological, and ecological – describing in more certain terms what this effort entails, how it best might be achieved, and where it can begin most easily.

As I will explore with you in concept and practice, and again confirming intuitions we have had for centuries, contemporary science underscores that happier and healthier life for all people is an outcome, endeavor, and indeed created condition that is at once realistic and waiting, with all or most of its needed features adequately understood and within our grasp (for a more careful summary and synthesis of this science, see Our Three Natural Paths and its free companion Three Paths Community Health Program).

Importantly, in our discussion, and as is my custom, I will take happiness as sustained positive feeling or emotion, and health as the more fundamental or ultimately selected natural quality that is sustainability or durability itself – and whether as respects an organism, group, species, or system. As a practical and empirical matter, happiness appears to follow health closely in nature, and also to be a general signal and motivator of health, especially in stable conditions of life.

Overall, the science of creating happier and healthier modern life suggests a three-part approach, or underlying model of action, and one employed simultaneously at the communal or local and societal or global levels. First, and fundamentally, is for us consciously to seek and prioritize these outcomes, and notably above all, which demonstrably is not evenly or even commonly the case today. Second, and unsurprisingly, is for us widely to use available empirical science to guide us in this naturally broad, complex, and overriding effort. Third, and given inevitable imperfection in our understandings and actions, is for us continually to adjust, improve, or evolve our sense and seeking of happiness and health, in order to achieve these core and related natural aims of life more readily, and more durably.

This three-part and only seemingly simple process for progressing modern happiness and health may strike you as obvious, even as it remains largely unused and overlooked in our time – with the natural, and naturally foundational, advancement of our health and ensuing happiness routinely subordinated to other goals, preoccupations, and formulations. As I have written about elsewhere, these alternative aims and efforts can be framed helpfully as surrounding or broadly emerging from the historically new, naturally isolated or indifferent, and discernably less happy and healthy phenomenon that is human competition for wealth. This now frequently dominating state of life in turn is well-approached as occurring in place of and keeping us from more widespread, more naturally advanced and advancing, and predictably more harmonious and enduring cooperation for health. Crucially, and as you can confirm for yourself, our exploration of conscious, scientific, and evolving human cooperation for health reliably leads us to the conclusion that we now collectively must live much more carefully or attentively with our science, with one another, with our natural happiness and health, and with health-bestowing nature.

These critical and observable premodern and modern social dynamics underscore that, although far happier and healthier life may be waiting for us in a scientific age, action in this direction must confront and overcome substantial barriers to realizing our new potential to design and build our communities, societies, and thus lives for transformed, and naturally transforming, happiness and health. As suggested, and as you will see in the science-derived construct or model for happier and healthier human life I will introduce, movement toward appreciably healthier or naturally superior conditions today appears to involve a basic shift and thus change in the general direction or emphasis of modern life and society. In practice, this means stopping a great deal of what we now do, and often making more than incremental or modest adjustments to the ways in which we currently think, organize, plan, design, build, and live.

Making these essential and life-altering ideas more pointed and palpable, and now specifically addressing those of us who plan, create, and finance our modern built environment as their profession, I concurrently and more emphatically would say this: there is something deeply flawed, irrational, self-limiting, far from optimal, recurrently unhappy and unhealthy, and thus unnatural in the ways that we design and build our communities, cities, and societies at present. Around the world, our existing planning, design, and development practices routinely and measurably squander natural resources and human effort, precariously pollute and impair our planet’s ecosystems, and simultaneously diminish our environment and ourselves. Relatedly, and again measurably, our development methods also frequently and now needlessly create insecure and unstable communities and societies, perpetuate strained and unsustainable human relations and conditions more generally, leave us individually less fit and well than we readily might be, and in all produce much less human happiness and health than is possible in our time – and naturally will be necessary in time.

Against these important and intersecting shortfalls in our modern design and development practices, our opportunity to plan and build life in superior and more advancing ways – and thereby naturally or quintessentially to create superior and more advancing conditions of health for all people, and even all of life around us – once more appears to begin from and depend on our new science-enabled ability to understand and construct life in more careful, deliberate, foreseeing, and beneficial ways. For all of us, but again especially those of us in and funding the design and development professions, this inevitably means better comprehending why and improving how we build the structures and thus structure of life, and in turn steadily and ultimately acting in ever more patient, informed, reflective, prospective, and health-minded terms.

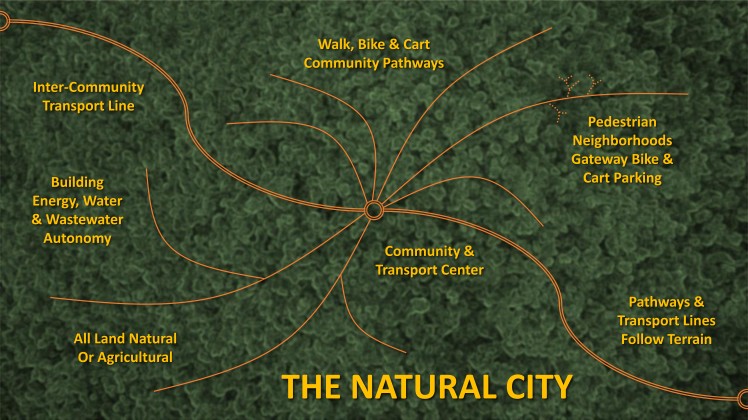

To consider these naturally essential and now pressing themes more deeply, concretely, and actionably, I will introduce and explore a science-synthesizing, healthfully-remaking, and far-reaching model for modern design and development, one that I call the natural city. As you will see, this alternative and remarkably simple approach to community and ultimately societal design makes clear, conceptually and practically, that my introductory ideas are substantially true and ready for urgent attention. As part of this discussion, the natural city model will demonstrate how an array of limiting and largely inherited shortfalls in modern quality of life can be simultaneously, systematically, and fairly easily remedied, beginning in our time, and again largely through superior or more health-minded design and development practices.

In keeping with my overview graphic above, and as you will see in our exploration of the city, the natural city is a tangible, practicable, and ready alternative to our dominant modes of community and societal design and development today. In all, the natural city aims at, and appears likely to produce, immediately much happier and healthier modern people, communities, and societies. At the same time, the natural city also aims at, and similarly appears likely to produce, human life that is recurringly or enduringly efficient and effective at achieving these core natural aims, leading to far more stable and sustainable conditions in time than is probable at present. Importantly, this increased stability and sustainability is for our societies and species, and interrelatedly, for all or much of natural life on our planet as well.

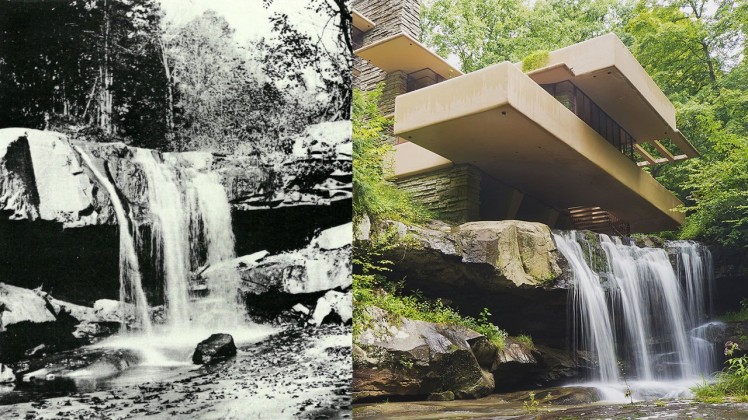

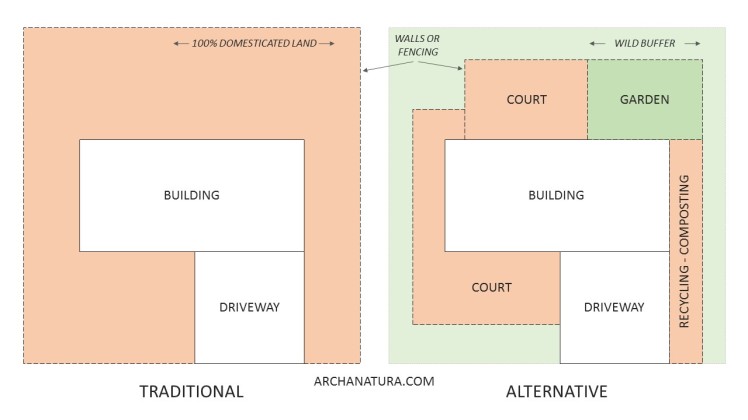

As its seemingly, and thus instructively, contradictory name implies, the natural city first is very much a city – though importantly, one envisioned as becoming societal and eventually global in scale – affording the social, economic, efficiency, and intellectual advantages of urbane, interconnected, dense, and cosmopolitan human life. At the same time, and in keeping with its name, the natural city also is an urban entity innovatively placed directly in and subordinated to the natural landscape. Owing to this second essential attribute, the natural city thereby is a construct seeking the reliable physical, emotional, perceptual, informational, and ecological benefits of human life in close proximity to and intimacy with the natural world, and not only to and with itself, as of course was our long, long-evolved, long-enduring, and health-advancing ancestral condition.